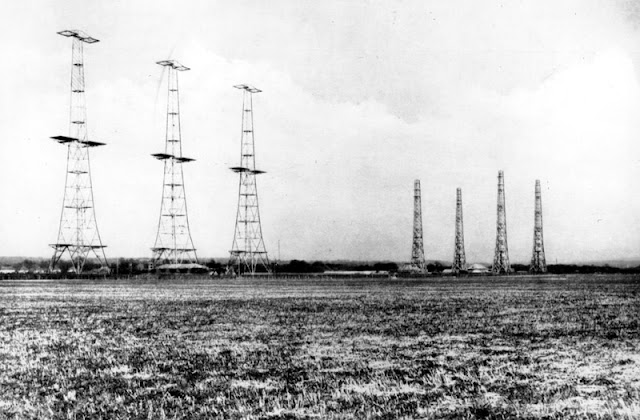

The second phase of the Battle of Britain began as the Luftwaffe expanded its targets to include British airfields. Bf 110s and Stuka dive bombers attacked radar installations along the coastlines of Kent, Sussex and the Isle of Wight, damaging five radar stations and putting one out of action for eleven days.

The Battle of Britain: During the day the Luftwaffe conducted raids on Portsmouth and the British airfields in Kent at Manston, Lympne, and Hawkinge. During the night there were widespread raids in small numbers occurred over the country. Minelaying was suspected off the North East and East Coasts and in the Thames Estuary and Bristol Channel.

Weather: Fine and clear during the morning, after early morning mist. Light cloud in the north giving way to lengthy sunny periods. Dry all day.

0840 hours: The day before the official Adlertag was due to commence, radar detected enemy aircraft approaching from the direction of Calais, it was not unusual for German bomber formations to fly directly overhead en route to their target area. But this time it was different, this was a highly skilled Bf 110 operation that now attacked the high towers of the British radar stations. Each of the Bf 110 carried a single 500kg bomb, and this elite squadron commanded by Hauptmann Walter Rubensdoerffer who split his gruppe into four groups of four Bf 110s. At first, he led the section on a westerly course, flying low in an effort to avoid detection, then just south-east of Beachy Head swung northwards and headed towards Eastbourne and the white cliffs of Dover that were now becoming more visible as the warmth of the morning burnt off the haze that was enveloping the British coast. At a pre-determined point, the raiders started to gain height so as to effectively dive bomb their targets, the British radar suddenly picked up the German formation but became bewildered as to where they had suddenly appeared. An excellent descriptive is given by Richard Hough and Denis Richards and is worthwhile quoting here:

Now Erpro 210 broke up into its four sections, and Rubensdoerffer himself set course for a more inland CH station, Dunkirk, northwest of Dover. Hauptmann Martin Lutz had been assigned the first and easiest target, Pevensey CH, right at the start of their run and dead ahead as they raced towards land. Oberleutnant Wilhelm-Richard Roessiger had been ordered to follow the coast east to the towering masts just beyond Rye, while Oberleutnant Otto Hintze with his four fighter bombers was deputed to knock down those provocative towers above Dover.

Lutz’s fighter-bombers dropped their eight 500Kg bombs dead on their Pevensey target at the end of a 300+ mph glide. They could scarcely miss. There was no opposition on the ground or in the air. Concrete buildings collapsed and spread their fragments widely, as if made of paperboard. Telephone lines were torn apart, airmen and WAAFs were killed and injured, smoke and dust rose from the craters. The noise was stupefying, and the awful silence and darkness that followed seconds later told of severed power lines — in fact, the main supply cable had gone.

At Rye along the coast, Roessiger’s foursome destroyed every hut, but as at Pevensey the reinforced transmitting and receiving blocks and the watch office survived though the personnel were severely shaken. The damage at Dunkirk, too, proved the success of Rubensdoerffer’s training: every bomb bang on target.

The Bf 109 and 110 formation was flying directly for Dover, then, as soon as they flew over the coast they suddenly turned and immediately attacked the tall towers of the radar installations. In a swift and precise move Dover CH was damaged and put off the air. The formation continued on to Pevensey, then Rye and then Dunkirk. Then Rye radar station also reported the sighting and reported it to Fighter Command. Immediately it was given an “X” code, a code that was used if a sighting was of doubtful origin or could not be properly ascertained. Later, when Fighter Command wanted to know what was happening down there, the radio operator radioed Pevensey and asked the question, to which a gentlemanly voice said “…your bloody unknown origin is kicking the shit out of us, that’s what”. The same question was put to Rye, where the WAAF telephone operator in a rather pleasant tone of voice simply said “….actually, your “X” code is bombing us “All these radar stations suffered considerable damage and were put out of action. (Dunkirk suffered minor damage but the other three were back on the air after just a few hours).

There was less doubt on the coast. Behind Daphne Griffith’s, the station adjutant, Flying Officer Smith, one of several officers who had drifted in to watch, recalled that the Ops hut was protected only by a small rampart of sandbags. He told Corporal Sydney Hempson, the NCO in charge: ‘I think it would be a good idea if we had our tin hats.’ At that moment the voice of Troop Sergeant Major Johnny Mason, whose Bofor guns defended the six acre site, seemed to explode in their headsets: ‘Three dive-bombers coming out of the sun — duck!’

It was split second timing. Along the coast, Test Group 210, split now into squadrons of four, came hurtling from the watery sunlight — Oberleutnant Wilhelm Roessiger’s pilots making for the aerials at Rye, Oberleutnant Martin Lutz and his men streaking for Pevensey, by Eastbourne, Oberleutnant Otto Hintze barely a thousand meters above the Dover radar station, flying for the tall steel masts head-on in a vain effort to pinpoint them, Rubensdorffer himself going full throttle for the masts at Dunkirk, near Canterbury.

Suddenly the Ops hut at Rye shuddered, and glass and wooden shutters were toppling; clods of earth fountained 400 feet high to splatter the steel aerials. Prone beneath the table, the WAAF crews saw chairs and tables spiral in the air like a juggler’s fast flying balls — everywhere the sites were under fire. At Pevensey, tons of gravel swamped the office of the C.O, Flight Lieutenant Marcus Scrogie, only minutes after he left it; at Dover, a bomb sheared past recumbent operators to bury itself six feet beneath the sick quarters. At Dunkirk, one of Rubensdorfer’s thousand-pounders literally shifted the concrete transmitting block by inches. All along the coast the tall towers trembled, and black smoke rose to blot out the sun.

But by midafternoon, General Wolfgang Martini, Luftwaffe signals chief, knew bitter disappointment. Operating with stand-by diesels, every station except Ventnor — a write off for three long weeks — was reported back on the air. To Martini, it seemed now as if radar stations could not be silenced for more than a few hours at a time.

The radar stations dotted all along the southern English coastline, easily picked out by the Luftwaffe pilots as the tall lattice-work towers stand out predominately along the coast, so visible, yet at the same time, so vulnerable, but they seemed almost immune to the high explosive. Although considerable damage was done, and the attack played havoc with the communications, but again, the Luftwaffe onslaught did not attain the success that it had anticipated. Dunkirk continued to transmit as did Pevensey and Dover, after only a brief interruption to communications. This was due to emergency stand by systems that had been included in the design of the radar stations. Standby diesel engines were started up to provide the power, while after any line breakages had been repaired all stations were soon back on the air again. But with the downed towers, the advance warning system had lost a considerable amount of effectiveness, with the Observer Corps doing most of the work.

Then came something very different, it was at Dover, suddenly the silence was broken by a dull whistle getting louder and louder, then a big bang with bricks, framework, dirt and dust going everywhere, military personnel as well as locals in the town nearby were stunned, there was not an aircraft to be seen…..anywhere. These were the first rounds of Germany’s long-range artillery fire. These big guns, located on the coast of France, projected their shells twenty-one miles across the Channel and landed right on target.

1145 hours: Rubensdoerffer reported that the mission was seventy-five percent successful, and Kesselring, to make sure that the RAF radar network was in chaos, sent out Ju 87 Stukas to attack several small convoys in the Thames Estuary. Although Fighter Command communications were stretched to the limit, Foreland CHL for some reason escaped the early morning attack by Rubensdoerffer and reported back to HQ that 50+ enemy aircraft had been picked up, with another force of 12+ that although separate from the main force were possibly intending to link up and attack the convoys of “Agent” and Arena” that were cruising in the Estuary. Hornchurch dispatched their 65 Spitfire squadron and Biggin Hill sent out the Hurricanes of 501 Squadron to intercept. It was not a good day for Fighter Command. Convoy “Agent” was attacked by the Ju 87s, and the Hurricanes that were trying to stave them off paid a high price. Four of them were shot down and two RAF pilots were killed.

Poling radar detected a large force of raiders over the Channel south of Brighton. This turned out to be a bomber force of Ju 88s of KG 51, escorted by Bf 110s of ZG 2 and ZG 76. Cover for the formation was provided by twenty-four Bf 109s of JG 53. In all, a total of 200+ aircraft. They kept to their westerly course following the coastline of Sussex until they were south of the triangular shape of the Isle of Wight, then the Kommodore of KG51 Oberst Dr Fisser kept his formation on a heading for Portland giving the RAF the impression that he was going to repeat the bombing of the Dorset town as he had done the previous day. But as the balloon defenses of Portsmouth came into view on his starboard side, he turned his formation northwards.

But there was still other radar stations operating, notably the important one at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, and this was to become the next target for the Luftwaffe, and at the same time, because of the major towns of Portsmouth and Southampton were nearby, attacks could be made on these at the same time. Richard Hough and Denis Richards continue:

Almost simultaneously with these convoy attacks off the Kent coast, Kesselring and Sperrle launched a ferocious attack on the center of England’s south coast, comprising — amongst much else — the naval bases of Portsmouth and Portland, the industries of Portsmouth and Southampton, including the Supermarine Spitfire works at Woolston, and the key radar station at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight.

The heart of this force comprised 100 Ju 88s of the Eidelweissgeshwader, KG51, based at Etampes, Orly and Melun-Villaroche. This force had taken off shortly before 11am. and made a rendezvous with its fighter escort half an hour later. One hundred and twenty Bf 110s of Zerstoerergeschwader 76 and 2, from other French airfields, accompanied the bombers north from the Normandy coast. Another twenty-five fighters, 109s of JG53, were then dispatched direct, in order to save fuel, to the target area where they were ordered to give top cover. These pilots, especially, found the long sea crossing a taxing exercise, knowing that they would have little more than ten minutes combat time to spare at their extreme limit of range before having to return, or ditch in the Channel…

Dowding, with Keith Park and Leigh-Mallory were on the mezzanine level of the operations room at Fighter Command HQ at Uxbridge, and were looking down on the huge map below. They looked eagerly at the situation and watched intensely as the WAAFs slowly moved the enemy markers towards the Isle of Wight and Portsmouth. Dowding remarked that ‘…..it’s obvious that they are trying to knock out our radar and communications’, no one acknowledged, they just kept their eyes glued to the map below. The action continues as KG51’s Kommodore Oberst Dr Fisser led his Geschwader west, some fifteen miles off the flat west Sussex coast with the triangular configuration of the Isle of Wight dead ahead:

He ordered his armada sharply to starboard, just as a man o’war might do, in order to enter Portsmouth Harbor through a gap in the balloons. Fisser and fourteen of his crack crews had other plans, though, and as he circled he watched his bombers going in like a huge serpent in line-astern.

The anti-aircraft fire, from every ship in the Harbor, firing for once from a steady gun platform, and from the Army’s guns ashore, was in its intensity like nothing Fisser, or any of his crews, had seen before — 4·7 and 4.5 inch, 3 inch, 2 pound pom-poms, Bofors and even 20mm filled the sky with black puffs and criss-crossing tracer. Now Fisser himself turned southwest, losing height and gaining speed rapidly as he raced at 300 mph and at 5,000 feet over Foreland, the eastern tip of the Isle of Wight, heading for the little seaside resort of Ventnor.

There, on a strip of high-level ground close to the town, were sited the tall towers of the CH station which covered the whole mid-Channel area, and whose screens were now scarred with the blips from Fisser’s main force and, more ominously, the detachment coming directly for the Station . Fisser wasted no time. Like Rubensdoerffer, he wanted to get in and out as fast as possible, and he aimed the nose of his Ju 88 at the towers and the buildings, all connected by a criss-cross pattern of white concrete paths which would have given away the target in much less favorable visibility. Like most 88 commanders, he favored the shallow dive approach which gave his bomb-aimer the best visibility and more time to make last split-second adjustments than in the 45 degree or steeper approach. Fisser saw no anti-aircraft fire, and it was almost impossible to miss with the four 250 kg, delayed-action, high-explosives they all carried.

Lighter by a ton, he pulled up steeply above the scattered boarding- houses and small hotels of the seaside resort, over the chalk cliffs and the breakers on the shore, and watched the bombs explode. Fisser was a veteran of the Polish and French campaigns, had dropped bombs across half of Europe (or so it sometimes seemed), but he could never have seen such concentrated devastation. The whole target was engulfed by white-and-black clouds, with more exuding from the inferno as he turned away and ordered his planes to close in, climbing at full throttle, to escape the avenging wrath of the British. But already the first reports were coming in from behind that still distant Hurricanes were diving towards them. And, belatedly, the Bofors anti-aircraft fire had burst into action — or perhaps it had been firing when they were all too preoccupied with their run-in. It was accurate firing, too, and as Fisser continued his turn overland north of Ventnor, he suddenly realized that his whole detached force was in a dangerous position, with a height disadvantage and only a scattering of Bf 110s to give them any support before they could clear the area.

McGregor’s Hurricanes were first on the Ventnor scene, as he had predicted, but 152 Squadron’s Spitfires came in seconds later, and a whirling fight ensued before Fisser could get his 88s away. McGregor himself got on the tail of a 110, ignoring the rear-gunner’s fire, and dispatched it with a single burst. Then two more of his squadron began harassing Fisser’s 88 and were joined by two more of 152’s Spitfires. The Kommodore was killed at the controls. The Junkers, trailing flames, dived towards the ground, was pulled up violently, presumably by one of the crew, and headed towards Godshill Park, yawing and only partly under control. It struck the ground heavily, sending up a cloud of pale earth, and slid to a halt, its back broken but the fire self-extinguished. Leutnant Schad and Oberleutnant Luederitz, both wounded, staggered from the wreckage, and their captors succeeded in extricating the fourth crewman, badly burned, a few minutes later. Most of Fisser’s Geschwader were still attacking Portsmouth at 12.25 p.m. as he lay dead in this pleasant park on the Isle of Wight a few miles away. The anti-aircraft fire remained intense and accurate throughout the Portsmouth attack. Ten more 88s fell to the RAF fighters’ guns, or the ground gunners (most likely both) besides McGregor’s 110 victim, which went into the sea off Foreland. By a curious freak of the tides in these uncertain waters, the body of Fritz Budig was washed ashore near Gosport, while his pilot’s body was found on the beach near Boulogne five weeks later.

Portsmouth was hit hard in this battle, shops, buildings and factories were destroyed, fires broke out in many parts of the city and falling walls and masonry became a hazard. This was the first major attack on an English populated area, and to the British, it was a sign of things to come. 100 civilians died, but as far as the air war was concerned, the British were still losing less than the Luftwaffe.

But Ventor radar was a shambles, it was now completely out of action. Dunkirk, Pevensey, Rye and Dover radar stations had suffered damage enough to put them out of action temporally, and this was a plus for the enemy, as both Kesselring and Sperrle were convinced that now the radar station attacks had achieved their purpose and that the RAF was now ‘without it’s eyes’. The Luftwaffe could now impose the next phase of the battle, and that was the destruction of the RAF airfields in southern England. The first three on the list was, Lympne, Hawkinge and Manston.

1325 hours: The airfield at Manston was the first to be hit. Rubensdoerffer’s Erpro210 was back again after the earlier damage it had done to Dover and Dunkirk radar stations. This time dropping bombs and machine gunning the satellite airfield just as 65 Squadron (Spitfires) were taking off on a routine patrol.

Manston, or ‘Charlie 3’ as this airfield was known, was the real prime target, it was the most easterly of all the airfields in the south, and another of the all grass airfields which allowed entire squadrons to take off together thus they were in the air and reaching the enemy quicker than if they had to take off in single file on any of the concrete runways.

54 Squadron Hornchurch (Spitfires) witnessed the whole of the attack from the air. The telephone rang outside dispersal at Hornchurch. “Okay fellas ‘scramble’….angels one-five Manston”. The same was to happen at Rochford, a satellite station of Hornchurch. A flight from 54 Squadron were lazily sleeping, reading or chatting outside dispersal when the telephone rang. ‘Jumbo’ Gracie turned and made a grab for the receiver, there was a silence as he listened, then at the same time as he banged the handset down he yelled “Scramble…. Seventy plus bandits approaching Manston… Angels one five.” In those few short words of pilots jargon, it painted a vivid picture to the scrambling pilots as to what to do and what to expect. Angels, in pilots language was thousands of feet, bandits was enemy aircraft and scramble was ‘drop everything and get to your waiting aircraft’. So the message was clear, get to your aircraft as quickly as possible, start engines, take off, and head in the direction of Manston in Kent where anything between seventy and eighty German aircraft were approaching at fifteen thousand feet.

Flight Lieutenant Al Deere who had been leading a flight out of Manston, a New Zealander was flying at about 20,000 feet when he spotted the attack. He immediately broke radio silence and called Pilot Officer Colin Gray, another New Zealander who was Blue Section leader, ‘Do you see them’, Gray was looking earthwards ‘Too bloody right,’ they were preparing to go in. Then, just as 54 Squadron was within striking distance of the mixture of Bf 109s and 110s, Deere saw that Blue leader was no longer with them. Gray had sighted a second formation that was approaching Dover and had already engaged them. Deere yelled over his radio, ‘…where the hell are you?’ Then he saw plumes of white smoke that was spiraling upwards from the aerodrome, he thought that the whole airfield was on fire, where instead it was only the white chalk dust from the many craters that were appearing all over the Manston airfield.

54 Squadron had managed to get off safely before the Erpro210 Bf 110s and Bf 109’s arrived and began an interception of the German formation, but 65 Squadron had an hair raising experience taking off as bombs exploded around them. Only P/O K.G.Hart in Spitfire R6712 was injured and his aircraft damaged in the attack. No sooner had 54 and 65 Squadrons pushed the Bf 110s and Bf 109’s back over the Channel, a formation of Dorniers from KG2 led by Oberst Fink came in over the Straits of Dover and headed for Manston. The airfield was now a shambles. It is estimated that 150 high explosive bombs fell, destroying hangars, workshops and damaging two Blenheims and the airfield finished up with more holes in the ground than an eighteen hole golf course.

Hawkinge suffered a similar fate with hangars and huts destroyed and twenty five large, and numerous small craters appearing all over the airfield, enough to put Hawkinge out of action for three days. Lympne also suffered in the attack.

Dowding and Keith Park again were in the operations room at Fighter Command HQ watching with great concern as the battle unfolded, they saw the WAAFs move the ‘enemy indicators’ from the Channel and in the Estuary across the coast and towards the airfields. Park complained that 501 Squadron that had just been ‘scrambled’ and that 64 Squadron who had already taken off were not yet in a position to attack them ‘….they’re not getting up quick enough, they’ll have to do better than that’ he said, ‘at least we know now what he’s after — my bloody airfields’. Dowding took the news on a more serious note, ‘…gentlemen, I think the battle has begun’.

1350 hours: What happened next in the life of a pilot, was typical of a scramble that could have taken place at any of Fighter Commands airfields, this is how Pilot Officer Geoffrey Page of 56 Squadron attacked the situation:

After the call of “Scramble”, there was no time for further reflection. As he pelted the fifty yards to his waiting Hurricane, the suspense was banished and Page’s mind was clear and alert, with only physical action to preoccupy him. Right foot in the stirrup step, left foot on the port wing, one short step along, right foot on the step inset in the fuselage, into the cockpit. Deftly his rigger was passing parachute straps across his shoulders, then the Sutton harness straps….pin through and tighten the adjusting pieces….mask clipped across and oxygen on. He had primed the engine, adjusting the switches, and now his thumb went up in signal to the mechanics. The chocks slipped away, the Rolls Royce Merlin engine roared into life, flattening the dancing grass with their slipstream, and Page was taxi-ing out behind ‘Jumbo’ Gracie.

The Hurricanes climbed steeply, gaining height at more that 2,000 feet per minute, and the voice of Wing Commander John Cherry, North Weald Controller, filled their earphones, calling ‘Jumbo’ Gracie: ‘Hullo Yorker Blue Leader, Lumber Calling. Seventy plus bandits approaching Charlie Three, angels one-five.’ Then Gracie’s high pitched voice acknowledged: ‘Hullo Lumber, Yorker Blue Leader answering. Your message received and understood. Over.’ One of the squadron’s pilots chipped in: lack of oil pressure was sending him home. Again Gracie acknowledged, and now ten Hurricanes swept on to intercept seventy German aircraft. Page thought idly, odds are seven to one — no better nor worse than usual. As they followed the serrated coastline of north Kent his altimeter showed 10,000 feet.

56 Squadron started to close in on the departing bombers, as Geoffrey Page later put it, like “an express train overtaking a freight train” and they started to attack. Unfortunately, Page’s Hurricane was hit and his aircraft exploded in a ball of flame. He managed to bail out, but badly burned was rescued by the Margate lifeboat.

Geoffrey Page was one of Fighter Command’s experienced pilots, that was to be out of the battle for a long time, like many others who had suffered burns, he was to have a long, long road to recovery. But, survival from severe burns is never going to be an easy one. But it is through such pilots as Geoffrey Page that we can learn what it is really like to experience what every pilot fears most, the thought of being trapped inside a burning aircraft.

It now seemed that the stage had been set. The Luftwaffe knew of the importance of the British radar, but they knew little about the basic fundamentals of how it was working for Fighter Command. They knew that the radar was the ‘eyes’ of the RAF, and that before making any attempt at engineering raids on RAF installations and facilities this radar had to be knocked out. They had tried, but only to find out that within hours, the radar stations were back in operational status once more. Even Ventor, which they thought had been totally destroyed, but to their surprise Britain had it back in operation within four weeks.

The early warning Radar chain was, in the main, so arranged that each stations area of detection was overseen by its adjoining stations, and so to cripple the system satisfactorily it was necessary to reduce the efficiency of two or three together. Much depended on how close the stations were to each other, e.g. in the south and southwest they were more widely spaced, making the cover less concentrated. There were mobile reserve units on call to plug gaps where enemy action had put Radar stations out of order or if cover suddenly became necessary in a hitherto unprotected area, but they were less effective than the original.

So, the plan was, that on August 12th they would knock out the radar installations at the key points of Dover, Pevensey, Rye, Dunkirk and Ventor so that the RAF would not be able to see that the next move was to destroy the RAF on the ground by bombing the airfields. With no radar to detect their approach, the way was clear for them send formations across the Channel, and the only way that they could be detected was by visual sightings, which by the time that this was made, it would be too late for the RAF to muster the aircraft needed to stop them before they had reached their targets.

Thirty-one German aircraft on this day were shot down, but it was not a day that favored the RAF as twenty-two fighter planes were destroyed and eleven pilots were killed.

RAF Statistics for the day: 196 patrols were flown involving 798 aircraft. Luftwaffe casualties: Fighters — 34 confirmed, 17 unconfirmed, 17 damaged; Bombers — 20 confirmed, 22 unconfirmed, 9 damaged for a total of 136 casualties. RAF casualties: 15 fighters shot down.

RAF Casualties:

1100 hours: Off Ramsgate (Kent). Hurricane P3304. 151 Squadron North Weald

P/O R.W.G. Beley Died of wounds. (Shot down by Bf 109. Crashed into sea and rescued. Taken to Manston)

1220 hours: South of Isle of Wight. Spitfire K9999. 152 Squadron Warmwell

P/O D.C. Shepley Missing in action. (Last seen in combat with Ju 88. Failed to return to base)

1220 hours: South of Isle of Wight. Spitfire P9456. 152 Squadron Warmwell

F/L L.C. Withall Missing in action. (Shot down by gunfire from Ju 88, believed crashed into sea)

1230 hours: South of Isle of Wight. Hurricane R4180. 145 Squadron Westhampnett

P/O J.H. Harrison Missing in action. (Shot down over Channel during combat with Ju 88s and Bf 109’s)

1230 hours: South of Isle of Wight. Hurricane P3391. 145 Squadron Westhampnett

Sgt J. Kwiecinski Missing in action. (Failed to return to base)

1230 hours: South of Isle of Wight. Hurricane R4176. 145 Squadron Westhampnett

F/L W. Pankratz Missing in action. (Shot down over Channel during combat with Ju 88s and Bf 109’s)

1235 hours: South of Portsmouth. Spitfire P9333. 266 Squadron Tangmere

P/O D.G. Ashton Killed. (Aircraft burst into flames from gunfire from enemy aircraft)

1245 hours: Off Bognor (Sussex). Hurricane P2802. 213 Squadron Exeter

Sgt S.G. Stuckey Missing in action. (Shot down over Channel by Bf 109s)

1245 hours: Off Bognor (Sussex). Hurricane P2854. 213 Squadron Exeter

Sgt G.N. Wilkes Missing in action. (Last seen in combat with Bf 109s. Failed to return to base)

1255 hours: Off Ramsgate (Kent). Hurricane P3803. 501 Squadron Gravesend

P/O K. Lukaszewicz Missing in action. (Shot down in Channel after combat with Bf 109s)

1300 hours: South of Portsmouth. Hurricane P3362. 257 Squadron Northolt

P/O J.A.G. Chomley Missing in action. (Last seen engaging Bf 109s. Failed to return to base)

RAF Bomber Command dispatches 6 Blenheims on a sea sweep in daylight, 1 aircraft bombed De Kooy airfield in Holland. No losses.

RAF Bomber Command dispatches 79 Blenheims, Hampden, Wellingtons and Whitleys overnight to 5 targets in Germany, to airfields in France, and minelaying. 4 Hampdens and 1 Blenheim lost. 4 O.T.U. sorties. 11 Hampdens of 49 and 83 Squadrons were ordered to make low-level bombing attacks on the Dortmund-Ems Canal at a point, near Monster, where the canal crosses the River Ems by means of twin aqueducts. These were an important bottleneck link in the German inland-waterway system. The aqueducts had been attacked by 5 Group Hampdens on previous occasions and damaged. The German defences had now been increased and low-level attacks were subject to intense light Flak. 2 Hampdens were shot down but 8 aircraft managed to drop their bombs and caused damage which was still holding up barge traffic more than a month later. For making a particularly determined attack, in which his Hampden was badly hit, Flight Lieutenant R. A. B. Learoyd of 49 Squadron was awarded Bomber Command’s first Victoria Cross of the war. The Dortmund-Ems canal would need to be attacked on many future occasions and a second Victoria Cross would be earned here in 1945, again by a member of 5 Group.

RAF Bomber Command also attacks the Gotha airplane factory and the airbase at Borkum. They also bomb the Black Forest with phosphorus and other incendiary bombs in an attempt to start fires which will burn away the cover from hidden bases there. This is called “razzle” and often ignites the planes themselves.

Bristol Beaufighters are delivered to Tangmere. They are the first fighters equipped with their own experimental radar.

RAF bombers again attack Tobruk.

At Malta, there is a bombing raid at 21:00 by two bombers that attack Hal Far airfield. There also are several other raids, with bombs dropped near Grand Harbour. Italian bombing aim is extremely poor, as many of their bombs land in the water. It is the first major raid since 26 July.

There is another invasion alert that brings the Home Fleet to 2-hours readiness at 22:17, but it is a false alarm.

It officially became illegal to waste food in the United Kingdom. The government has been encouraging “Victory Gardens” and the like for months due to the growing food shortage. Now, it takes a different tack and simply makes the wasting of food illegal.

The issue of starvation in Europe has been brought to the public’s attention by Ambassador Cudahy’s recent statements (for which he was recalled). Now, former President Herbert Hoover, who made his reputation in similar circumstances during World War I, begins a new war-relief program to send hundreds of thousands of tons of food to Europe.

The Belgian Government-in-exile opens a recruiting office in London.

Hitler officially accepts Mussolini’s offer to send Italian aircraft to assist Luftwaffe operations against U.K.

The Military Collegium of the Soviet NKVD sentenced Red Army divisional commanding officer Grigoriy Fyodorovich to death for deserting his unit in combat during the Winter War.

The Soviet Red Army slightly reduces the power of the political commissars which accompany each unit. Heretofore they have had equal authority over military operations, but now they are restricted to other matters. Military ranks are restored.

The Italians resume their attacks in the Battle of Tug Argan against the remaining five hills occupied by the Northern Rhodesian Regiment that overlook the vital coast road to Berbera. They take one of the hills, Mill Hill, from the Northern Rhodesia Regiment, including two 3.7 inch howitzers. The Italians already have successfully leveraged the British out of the south side of the defenses in the Assa Hills.

The British remain firmly entrenched to the north of the road. The odds are firmly against them, as 20,000 well-equipped Italian soldiers face about 4,000 colonial troops.

The British send men from Sudan into Abyssinia under Colonel Sandford to prepare the way for the return of King Haile Selassie. Sandford’s men train guerrilla forces.

Heavy cruiser HMS Norfolk and Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia departed Scapa Flow to patrol north of the Faroes for German shipping. The cruisers were relieved by anti-aircraft cruisers HMS Naiad and HMS Bonaventure and returned to Scapa Flow after an uneventful patrol on the 16th. The anti-aircraft cruisers patrolled until returning to Scapa Flow on the 20th.

The Home Fleet at Scapa Flow was brought to two and a half hour’s notice at 2217.

Destroyer HMS Watchman was damaged by near misses of air bombs north of Ireland. She spent no time out of service, but proceeded later in the month to Hull for refitting.

Destroyer HMS Garth departed Greenock at 1750 to join convoy WN.7 and proceed with it to Methil.

Destroyer HMS Vanity completed her conversion to escort vessel.

Minesweeping trawlers HMS Pyrope (295grt, Temporary Skipper A. J. Folkard RNR) and HMS Tamarisk (545grt, Skipper S. C. W. Bavidge RNR) of Minesweeper Group 2 were sunk by German bombing off North East Spit Buoy in the Thames Estuary. Six ratings were lost on trawler Pyrope. Seven ratings were lost on the trawler Tamarisk.

British trawlers Ermine (181grt), Kerneval (172grt), River Ythan (161grt) were damaged by German bombing off Smalls.

Italian submarine Malaspina sank British tanker British Fame (8406grt), which had been dispersed from convoy OB.193, in 37-44N, 22-56W. Three crewmen were lost and one was taken prisoner from the British tanker. The Portuguese destroyer Dao proceeded to assist.

Destroyers HMS Nubian, HMS Mohawk, HMS Imperial, and HMS Hostile departed Alexandria at 0600 on an anti-submarine sweep MD 6. Light cruiser HMS Neptune and Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney departed Alexandria at 0700 on an anti-shipping sweep and to provide cover for the destroyers. Light cruisers Neptune and Sydney and destroyer Imperial arrived back at Alexandria on the 14th. Destroyers Nubian and Hostile remained at sea to search for submarine Micca which unsuccessfully attacked light cruisers in 32-06N, 28-31E. Destroyers Nubian and Hostile arrived back at Alexandria on the 15th.

German steamers Quito (1230grt) and Bogota (1230grt) arrived at Yokohama.

The Italian submarine Iride departs La Spezia, Italy for Libya with four manned torpedoes on board.

Convoy OB.197 departed Liverpool escorted by destroyer HMS Mackay, sloop HMS Leith, corvette HMS Heartsease from 13 to 16 August. The destroyer and the corvette were detached to convoy HX.63.

Convoy FN.250 departed Southend. The convoy arrived in the Tyne on the 14th.

Convoy MT.138 departed Methil. The convoy arrived in the Tyne later that day.

Convoy FS.250 departed the Tyne, escorted by sloops HMS Black Swan and HMS Hastings. Patrol sloop HMS Guillemot joined on the 13th. The convoy arrived at Southend on the 14th.

Convoy HX.65 departed Halifax escorted by Canadian destroyer HMCS Assiniboine and auxiliary patrol boat HMCS French at 1540. Convoy SHX.65 departed Sydney, CB escorted by Canadian destroyer HMCS Saguenay and auxiliary patrol boat HMCS Laurier. They joined HX.65 at sea. At 1940, French was ordered to return to Halifax. Destroyer Assiniboine arrived back at Halifax at 0645 on the 14th after turning over the convoy to armed merchant cruiser HMS Voltaire. The armed merchant cruiser was detached on the 23rd.

Convoy BHX.65 departed Bermuda on the 11th escorted by ocean escort armed merchant cruiser HMS Montclare. The convoy rendezvoused with convoy HX.65 on the 16th and the armed merchant cruiser was detached. On 24 August, destroyers HMCS Skeena and HMS Westcott and corvette HMS Godetia joined the convoy. Sloop HMS Lowestoft joined on the 26th. They arrived with the convoy on the 27th at Liverpool.

Today in Washington, the Senate debated the Burke-Wadsworth compulsory military service bill, heard Senator Hatch criticize the distribution of campaign books by the Democratic National Committee, and recessed at 5:27 PM until noon tomorrow.

The House approved the conference report on the Wheeler-Lea Transportation Bill, tabled the Rogers Resolution calling for a weekly report on progress of the national defense program, and adjourned at 4:31 PM until noon tomorrow.

The Ways and Means Committee heard additional witnesses on the proposed excess-profits tax bill, and the Military Affairs Committee considered the National Guard mobilization bill.

A prediction by Senator Norris, Nebraska Independent, that peace-time conscription would result in “dictatorship” brought Senator Burke, Nebraska Democrat to his feet today to declare that, on the contrary, it was “the only democratic way to provide an adequate national defense. “It recognizes the obligation of all to serve, and to adequately train for that service,” said Burke, a co-author of the pending bill. “Rich and poor, all classes, races and creeds are treated with exact and equal justice. Instead of being contrary to the principles of American liberty and freedom, this proposal Is implicit with the spirit of true Americanism.” Norris had previously told the senate with characteristic fervor that “compulsory military training in time of peace cannot long prevail in a democratic form of government without leading that government into the realm of dictatorship.” He predicted a huge standing army, militarism extending into the years, and women eventually working in the fields to support the men in uniform, as consequences of the passage of the bill.

The Senate’s second day of debate on the subject of conscription also produced a charge by Senator Wheeler, Montana Democrat, that Henry L. Stimson is “unfit” to serve as secretary of war, an assertion by Senator Vandenberg, Michigan Republican, that voluntary enlistments should be given a further trial before sorting to conscription, and a statement by Senator Clark, Missouri Democrat, that the army favors the bill because it would mean swift promotions for the present officer personnel.

It was reported in congressional circles to night that President Roosevelt is carefully weighing proposals for the sale or trade of 50 over-age destroyers to Great Britain but that he will not act until he has advance assurances that congress will approve. According to United Press informants, the administration is taking soundings on potential opposition in both houses. At the same time, it was reported, several executive departments are surveying legal obstacles which would have to be removed. There are four such obstacles at present: The Hague covenant of 1911; a 1917 law prohibiting government sale of war materials to belligerents; the neutrality law banning unneutral acts, and a recently enacted measure requiring the certification as “surplus” of all defense materials proposed for sale. All of these hurdles could be surmounted, it was said, if congress gave advance assurance that such sale or exchange would be ratified.

The State Department has no intention of appealing to Great Britain to lift her blockade sufficiently to facilitate feeding the peoples of France, Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium, if the reaction today to the statement of former President Herbert Hoover on the subject is any criterion.

The Dies House Committee on un-American Activities, Secretary Robert E. Stripling said today, will investigate a list of nearly 1,200 German-American bund sympathizers in its possession. “The list was turned over by Herman Schwinn, Los Angeles bund leader, to James Stedman, chief investigator for the committee,” said Stripling, “after it had been testified in Washington that the bund had thousands of official sympathizers not actually members of the bund. “These are people who supposedly paid a dollar a year and signed a card as persons sympathetic to blind activities. It will be interesting to this committee to find out what occupations these persons are now engaged in.”

Attorney General Jackson, commenting on a reported plan to distribute the Democratic 1940 campaign book through state and county organizations, said today that the Justice Department did not believe that “state laws could make permissible that which a federal law prohibits.”

Herbert Hoover will make several campaign “talks” for Wendell L. Willkie during the coming campaign, according to a statement by the nominee today.

The known death toll in yesterday’s hurricane along the Georgia and South Carolina coast rose to thirty-five tonight and rescue crews penetrated further into the stricken areas. Property damage was in the millions of dollars.

U.S. President Roosevelt departed Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, United States aboard presidential yacht Potomac, escorted by destroyer USS Mayrant, for Newport, Rhode Island, United States to inspect the Torpedo Station and the Naval Training Station with Secretary of the Navy Knox, Senator David I. Walsh and Rear Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus. He then sailed for the Submarine Base at New London, Connecticut, United States, inspecting submarine operations en route and visiting Electric Boat Company facilities in New London. Finally, he set sail for Washington Navy Yard, Washington DC, United States, arriving at night.

The U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance requests informally that the National Defense Research Committee sponsor development, on a priority basis, of proximity fuses with particular emphasis on anti-aircraft use.

Ernest Lawrence Thayer, author of “Casey at the Bat” dies in Santa Barbara, California at age 77.

Major League Baseball:

Cleveland and Detroit‚ deadlocked for 1st place in the American League (64-44)‚ square off. In the initial pitching duel between the two aces‚ Bob Feller tops Hal Newhouser‚ 8–5‚ to become the majors’ first 20-game winner. Cleveland jumped out to an early 3-0 lead as Hal Trosky hit a two-out, two-run homer in the first inning and Beau Bell followed with a solo blast. After a Ken Keltner double, Newhouser was hooked and replaced by Clay Smith. An RBI-double from Pinky Higgins cut the Indians lead to 3-1 in the second, but the Indians got the run back in the fourth on an RBI-double of their own from Ray Mack that scored Keltner from first. Cleveland eliminated any doubts in the bottom of the fifth with a two-run homer from Roy Weatherly and an RBI-double from Bell that scored Lou Boudreau from second. With the bases loaded and nobody out, Smith was able to get a pop up to second and a pair of strikeouts to evade further harm. Higgins would drive in another run in the sixth, but a single from Boudreau in the bottom of the inning scored Ben Chapman to make it an 8-2 game. The Tigers scored three in the following inning, but would get no closer as Feller completed the game, allowing five runs on seven hits with five walks and seven strikeouts.

Jimmy Webb’s double in the ninth inning after Bob Kennedy walked and Clint Brown sacrificed him to second gave the White Sox a hard-earned 6–5 victory over the Browns tonight. The victors left seventeen men on the bases, one short of the league record.

The rampaging Pirates maintained their hot pace tonight by beating the Reds and Bucky Waiters, 4–2, before an excited crowd of 42,254 fans that overflowed into the outfield. It was the Corsairs’ eleventh triumph in twelve games and moved them to a game and a half of the third-place Giants.

Detroit Tigers 5, Cleveland Indians 8

Cincinnati Reds 2, Pittsburgh Pirates 4

Chicago White Sox 6, St. Louis Browns 5

U.S. Navy gunboat USS Erie, with Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt aboard, arrived at Guayaquil, Ecuador for a goodwill visit.

New arrests of foreigners were reported today amid a flare-up of anti-British feeling in Tokyo and signs of official pressure on other nations to withdraw from China. Domei, Japanese news agency, reported that nineteen foreigners had been arrested at Dairen, in the Japanese-leased territory of Kwangtung, on charges of disseminating anti-Japanese propaganda and possessing short-wave radios. Their names and nationalities were not disclosed. Most persons previously jailed in Korea and Japan proper in an anti-espionage campaign have been British. About 3,000 demonstrators at an anti-British mass meeting beneath German, Italian and Japanese flags were restrained by police from marching on the British Embassy in Tokyo.

They adopted resolutions demanding Britain’s full withdrawal from the Far East and advocating closer Rome-Berlin-Tokyo ties. Britain already has announced her decision to transfer her troops from China. Before the meeting convened, Yakichiro Suma, Foreign Office spokesman, had hinted that other nations should consider withdrawing their military forces from China. Britain’s decision, Mr. Suma said, emphasized that Japan was assuming responsibility for peace and order at Peiping, Tientsin and Shanghai and that, “because of changed conditions, it now was problematic whether it was necessary to maintain troops in those areas.”

The Japanese mission in French Indo-China has requested permission for the transport of troops and military supplies over the French railroad from Haiphong to Kunming in Southeast China and wants to erect a radio station at Hanoi to afford direct contact with Tokyo and Canton, it was understood here today. The Japanese mission is reported to have requested the expulsion of all Chinese from Indo-China if they have not been residents there for more than ten years, and a reduction in taxes and tariffs to aid Japanese merchants in the French colony. An estimated $8,000,000 worth of trucks, gasoline and other supplies was said to lie on the idle docks at Haiphong while French authorities, presumably on Japanese insistence, refused re-export licenses.

Dow Jones Industrial Average: 127.26 (+0.27)

Born:

Michael Brunson, English journalist, newscaster and actor (“Never Say Die”), in Norwich, England, United Kingdom.

Alexander Yossifov, Bulgarian conductor and composer (“Back To The Beginning”), in Sofia, Bulgaria (d. 2016).

Naval Construction:

The Royal Australian Navy Bathurst-class minesweeper-corvette HMAS Bendigo (J 187) is laid down by the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co. Ltd. (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia).

The Royal Canadian Navy Flower-class corvette HMCS Moose Jaw (K 164) is laid down by the Collingwood Shipyards Ltd. (Collingwood, Ontario, Canada).

The Royal Navy Fairmile B-class motor launch HMS ML 113 is commissioned.

The U.S. Navy prototype (163-foot steel hull) submarine chaser USS PC-451 is commissioned. Her first commanding officer is Lieutenant Joe Wood Boulware, USN

The Royal Navy Flower-class corvette HMS Anemone (K 48) is commissioned. Her first commanding officer is Lieutenant Commander Humphry G. Boys-Smith, RNR.